Amidst recent pushback to protect internet freedoms, it remains to be seen if Timor-Leste will retain its high rankings in “freedoms” in the long-term, as the country seeks membership in ASEAN, a grouping whose freedom rankings exhibit a sharp decline. While the country ranks highly in terms of academic and press freedom, with internet freedom likely to be on a similar upward trajectory, access to the internet and emerging laws present a challenge.

These were the broad assertions made during an online town hall titled “Timor-Leste: Internet Freedoms Under Threat” held on 4 June 2021 by Asia Centre to share its preliminary findings on internet freedoms in Timor and Southeast Asia (watch here) and gather feedback and recommendations in preparation of Timor-Leste ‘s Third Cycle UPR submission.

A key challenge to realising internet freedoms in Timor-Leste is its telecommunication infrastructure. With cable connections limited, signals unstable and access expensive in part as a result of limited competition among service providers, there is a correlation between the state of infrastructure and ensuring better access to information. Timor-Leste is currently expanding its internet and cable infrastructure and has approved connecting to Australia’s network at an estimated cost of between 40 to 60 million ($USD).

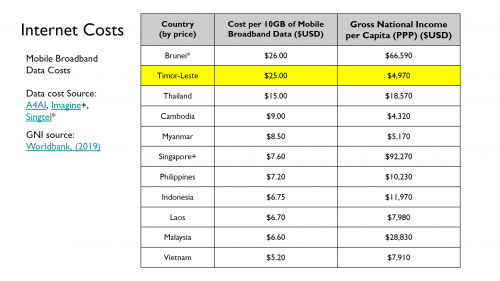

The majority of Timor’s citizens rely on the cellular network to access the internet, however the cost is incredibly high relative to the Gross National Income of its citizens. For example, a block of 10GB of Mobile Broadband Data is USD $25 in Timor with a GNI (PPP adjusted) of $4,970, while in Indonesia it is $6.75 and $11,970 respectively. Overall, the cost of accessing the Internet in Timor-leste is the highest in Southeast Asia by a significant margin.

The majority of Timor’s citizens rely on the cellular network to access the internet, however the cost is incredibly high relative to the Gross National Income of its citizens. For example, a block of 10GB of Mobile Broadband Data is USD $25 in Timor with a GNI (PPP adjusted) of $4,970, while in Indonesia it is $6.75 and $11,970 respectively. Overall, the cost of accessing the Internet in Timor-leste is the highest in Southeast Asia by a significant margin.

Yet as internet connectivity improves in Timor, the question of whether the country will follow the path of its ASEAN neighbours in restricting internet freedoms, or continue on her democratic trajectory remains.

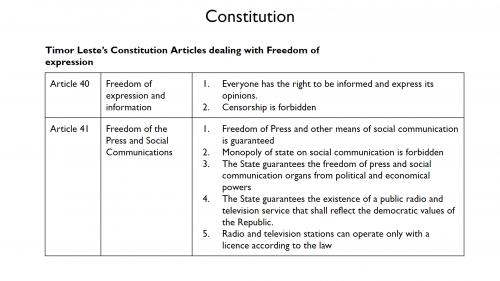

Improving telecommunications infrastructure and accessibility in Timor-Leste has led to the rise of the internet being used to express opinion, scrutinise political incumbents and progress democratic ideals. While Article 40 and 41 provide guarantees on freedom of expression, there is a push in Timor-Leste to reinstitute criminal defamation through draft laws in 2020 (Criminal Defamation) and 2021 (Cybercrime Bill).

Improving telecommunications infrastructure and accessibility in Timor-Leste has led to the rise of the internet being used to express opinion, scrutinise political incumbents and progress democratic ideals. While Article 40 and 41 provide guarantees on freedom of expression, there is a push in Timor-Leste to reinstitute criminal defamation through draft laws in 2020 (Criminal Defamation) and 2021 (Cybercrime Bill).

These laws, primarily articulated by those criticised authorities, seem to be aimed at curbing any just critique or debate. Often, the reasons behind these draft laws have been articulated either by those who feel hurtful, or were not used to the level of transparency and accountability required for an office holder; rather than for the benefit of the community as whole. While the draft law on criminal defamation faced pushbacks from civil society actors and the general populace and appears to be on hold at the moment. The sentiment in Timor that these laws will be implemented is strong.

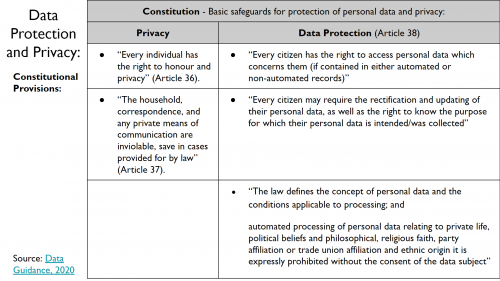

With increasing internet use, issues of data protection are an emerging concern. While Constitutional provisions are present to protect personal data and privacy in Articles 36, 37 and 38, they are considered insufficient. There is a need to ensure that personal data collected is not misused to persecute individuals who share critical opinions of the state, and that data is not shared without permission, as it has done by its ASEAN neighbours.

Data protection measures implemented should focus on the rights of individuals, with strong independent oversight mechanisms. It is expected that Timor-Leste will examine new Data Protection laws, however, if we look across Southeast Asia, this trend of legislating against critics is further entrenching and empowering the authoritarian regime. Something that Timor-Leste needs to avoid.

Data protection measures implemented should focus on the rights of individuals, with strong independent oversight mechanisms. It is expected that Timor-Leste will examine new Data Protection laws, however, if we look across Southeast Asia, this trend of legislating against critics is further entrenching and empowering the authoritarian regime. Something that Timor-Leste needs to avoid.

Increased internet access has unfortunately resulted in the proliferation of the traditional yet negative cultural notions with which women are generally viewed in Timorese society, for example domestic violence is sadly considered by both men and women as an acceptable form of discipline. This attitude has manifested online in rising hate speech and threats of violence against young girls and women. Laws to protect women and other vulnerable groups on the internet need to be in place and strengthened. Additionally, digital and media literacy in public institutions such as schools and universities should be a matter of priority in order to tackle the issue at the root, particularly against the backdrop of growing internet usage and connectivity in Timor.

Timor’s efforts to improve connectivity and introduce new legislation that may curb freedom of expression is a struggle over its own values that led to its independence. Yet, in pursuing accession to ASEAN, an organisation dominated by authoritarian states, the emergence of these proposed draft laws is a concerning hint at Timor-Leste’s new conflict with its own democratic identity.

Resistance from civil society groups has been encouraging, yet based on trends in the region it is not difficult to envisage the end result will be a less democratic Timor. Time will tell. As Timor-Leste aspires to be part of ASEAN, it needs to ask itself a hard question whether it wants to join the authoritarian club and behave the same.

The event, which was live-streamed, occasionally intervened by representatives from the Timor ICT department and attended by participants from Timor-Leste and Australia, is part of a series of consultations to gather feedback on the Asia Centre’s report on internet freedoms in the country.

Asia Centre works on issues related to freedom of expression. If you like to collaborate with the Centre on evidence-based research, co-coveneing activities or other projects. Send an expression of interest to contact@asiacentre.org